In the previous article of this series, we saw how to extract WAL records related to the exact SQL commands we want, INSERTs on heap tables, and what the structure of those records was. In this article we will focus on the heap specific information contained in those records and how to extract SQL queries from them.

INSERT data

At the end of the previous article, we could locate the various

xl_heap_insert records from the WAL stream. From there, we extracted some

metadata about the file’s physical location (tablespace oid, database oid and

relation filenode among other things) and the data that was inserted itself.

As a reminder, here’s an extract of the code responsible for generating the WAL records for an INSERT, in the heap_insert() function, focusing on the interesting data:

void

heap_insert(Relation relation, HeapTuple tup, CommandId cid,

int options, BulkInsertState bistate)

{

[...]

xl_heap_header xlhdr;

[...]

xlhdr.t_infomask2 = heaptup->t_data->t_infomask2;

xlhdr.t_infomask = heaptup->t_data->t_infomask;

xlhdr.t_hoff = heaptup->t_data->t_hoff;

[...]

XLogRegisterBuffer(0, buffer, REGBUF_STANDARD | bufflags);

XLogRegisterBufData(0, (char *) &xlhdr, SizeOfHeapHeader);

/* PG73FORMAT: write bitmap [+ padding] [+ oid] + data */

XLogRegisterBufData(0,

(char *) heaptup->t_data + SizeofHeapTupleHeader,

heaptup->t_len - SizeofHeapTupleHeader);

[...]

2 entries are inserted: an xl_heap_header which contains some metadata about

the tuple, extracted from the tuple header, and the data part of a

HeapTuple. Let’s look at those in details.

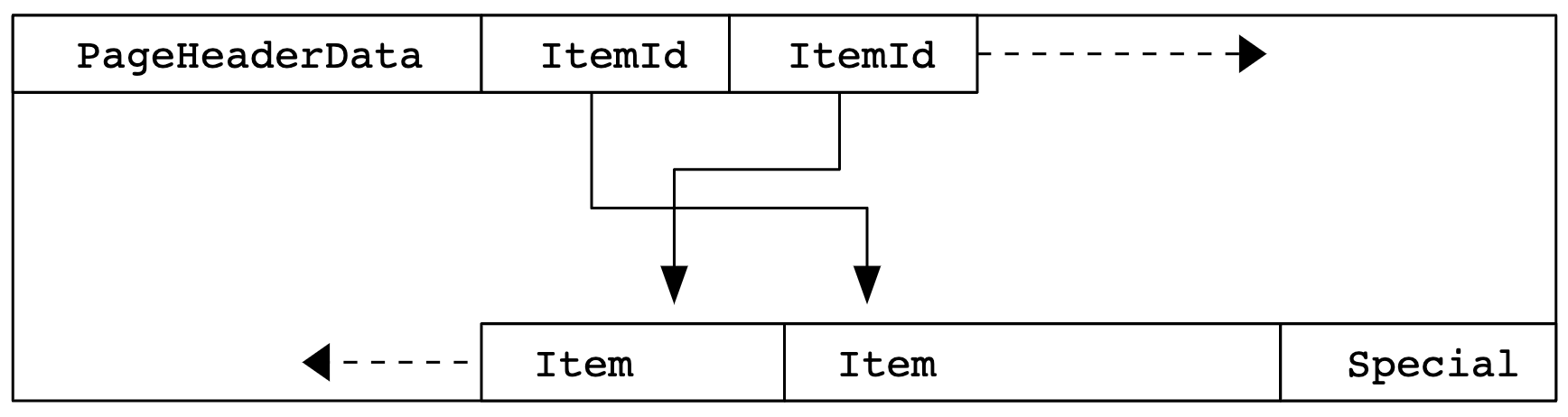

Page layout

First of all, let’s quickly see how postgres stores tables and indexes on disk. I will only cover those basics that will be helpful for the rest of the article. If you want to dig more into this topic, there are a tons of resource available. You can refer to this entry point in the code, and I otherwise recommend looking at the section about it in “The internals of postgres” website.

A good general introduction is the documentation, which comes with a diagram of the layout that I include here:

Each tuple and index piece of data that postgres stores on disk is stored into

a Page, which is by default 8kB. Each page starts with a header that

contains some metadata about the page and ends with an optional “special area”,

which can contain additional information specific to the component of postgres

that will use this page.

In between is the actual data. The beginning of the data part is an array of

ItemId, in ascending order, and the end of the data part are the items

themselves (which will be the tuples in case of heap table pages), stored in

the reverse order from the ItemId. Unless the page is totally full, there

will be an empty space between the last ItemId and the first item (the

pd_lower and pd_upper offset in the Page metadata).

Here’s the ItemId definition:

typedef struct ItemIdData

{

unsigned lp_off:15, /* offset to tuple (from start of page) */

lp_flags:2, /* state of line pointer, see below */

lp_len:15; /* byte length of tuple */

} ItemIdData;

As you can see it holds the location of the item in the page, minimal metadata and the length of the item.

HeapTuple

The largest part stored in the record is the tuple itself. As the historic and

default access method to store tuple is called heap, the struct that holds

the tuple is called HeapTuple. Any custom Table Access Method can use a

different struct to store what it needs for its specific implementation, but it

will then also use a custom resource manager to generate specific WAL records.

Here’s the definition of a HeapTuple:

typedef struct HeapTupleData

{

uint32 t_len; /* length of *t_data */

ItemPointerData t_self; /* SelfItemPointer */

Oid t_tableOid; /* table the tuple came from */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEDATA_DATA 3

HeapTupleHeader t_data; /* -> tuple header and data */

} HeapTupleData;

It starts with some metadata, which isn’t stored on disk but generated or

retrieved from somewhere else when the struct is read from disk. Indeed, there

wouldn’t be much value storing the relation’s oid for each tuple on disk. The

length of the tuple is stored on disk, as it’s a necessary piece of

information, and is retrieved from the associated ItemId the we saw just

before.

After that follows the “real” data, which is what is stored in the item

part of the Page. It’s again split in 2 parts: the tuple header, which I

will cover a bit later, and the tuple data.

The tuple data is the physical on-disk representation of the tuple. It was designed to be as space efficient as possible, so accessing individual fields is a bit complex, and CPU intensive. Let’s the most important part of this design. First, the tuple data is defined like that:

struct HeapTupleHeaderData

{

[...]

/* ^ - 23 bytes - ^ */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_BITS 5

bits8 t_bits[FLEXIBLE_ARRAY_MEMBER]; /* bitmap of NULLs */

/* MORE DATA FOLLOWS AT END OF STRUCT */

};

You probably know or heard that in postgres, NULL attributes don’t use any

storage. Indeed, if an attribute is NULL there won’t be anything in the “data

section”, and the bit for its attribute number in the t_bit bitmap will be

set.

Then, a lot of data types have a variable size (which is internally referred as

varlena). So, to save space postgres doesn’t store the offset of each

attributes in the HeapTuple and just stores them next to each other

(according to the datatype alignment rules) in a big chunk of memory.

This is indeed efficient, but unless your tuple only contains non-null fixed-sized attribute, the only way to access a specific attribute is to read all the previous ones, skip the NULL attribute and compute the position of the next one reading the length of variable datatype. This process is called tuple deforming, it takes a tuple in input and outputs two arrays: one with the datums and one with the null references, all indexed by the attribute number (0 based). The opposite operation (transform a tuple of datum and a tuple of nulls in a tuple) is unsurprisingly called tuple forming. If you want to read a bit more about those operations, the underlying functions are called heap_deform_tuple() and heap_form_tuple().

Note that tuple deforming is one of the operations that can be JITted, and there are some optimisations on the tuple deforming operation. Postgres supports “partial” deforming and will avoid deforming the full tuple when possible, stopping at the last attribute that the query is referencing, and will cache the offset of the latest attribute that has been deformed. But that can only help to some extent, so it’s always a good idea to mark columns as NOT NULL when possible, put all the columns with fixed-length attributes at the beginning of the tuples (with the NOT NULL first), ideally grouped by alignment size to avoid wasting a few bits, and put the most frequently accessed columns of variable length datatype next. All of that will help speeding up tuple deforming as much as possible.

Tuple header

The first part of the stored data is an xl_heap_header struct. It’s just a

shorter version of the real tuple header that only contains some part of it, the

rest of the header being available elsewhere in the WAL record or just not

needed otherwise. Doing it this way can save a few bytes for each insert in

the WAL, which is always a good thing. Its definition is:

typedef struct xl_heap_header

{

uint16 t_infomask2;

uint16 t_infomask;

uint8 t_hoff;

} xl_heap_header;

t_infomask2 and t_infomask2 are two bitmaps that contain information about the tuple. You may have heard about hint bits, those two fields contains the tuple-level hint bits.

Let’s look at their details htup_details.c

struct HeapTupleHeaderData

{

[...]

/* Fields below here must match MinimalTupleData! */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_INFOMASK2 2

uint16 t_infomask2; /* number of attributes + various flags */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_INFOMASK 3

uint16 t_infomask; /* various flag bits, see below */

#define FIELDNO_HEAPTUPLEHEADERDATA_HOFF 4

uint8 t_hoff; /* sizeof header incl. bitmap, padding */

/* ^ - 23 bytes - ^ */

[...]

}

* information stored in t_infomask2:

*/

#define HEAP_NATTS_MASK 0x07FF /* 11 bits for number of attributes */

/* bits 0x1800 are available */

#define HEAP_KEYS_UPDATED 0x2000 /* tuple was updated and key cols

* modified, or tuple deleted */

#define HEAP_HOT_UPDATED 0x4000 /* tuple was HOT-updated */

#define HEAP_ONLY_TUPLE 0x8000 /* this is heap-only tuple */

#define HEAP2_XACT_MASK 0xE000 /* visibility-related bits */

[...]

* information stored in t_infomask:

*/

#define HEAP_HASNULL 0x0001 /* has null attribute(s) */

#define HEAP_HASVARWIDTH 0x0002 /* has variable-width attribute(s) */

[...]

#define HEAP_XMIN_COMMITTED 0x0100 /* t_xmin committed */

#define HEAP_XMIN_INVALID 0x0200 /* t_xmin invalid/aborted */

#define HEAP_XMIN_FROZEN (HEAP_XMIN_COMMITTED|HEAP_XMIN_INVALID)

#define HEAP_XMAX_COMMITTED 0x0400 /* t_xmax committed */

#define HEAP_XMAX_INVALID 0x0800 /* t_xmax invalid/aborted */

[...]

We can see a few bits useful for the tuple deforming. For instance, we see that 11 bits of t_infomask2 are used to store the actual number of attributes stored in this tuple. Adding a new column in a table doesn’t always require a full table rewrite, and in that case those bits are critical to know when to stop looking for additional attributes when accessing tuples stored before the column was added. There’s also information on whether the tuple contains any NULL or variable-length datatype attribute. The rest of the hint bits are a clever use of the available space to handle various SQL operations, MVCC rules, HOT updates and other low level optimisations.

Tuple descriptors

Now that we covered some internals of the HeapTuple, it seems much easier to

reach our goal: transform the INSERT WAL records into plain SQL statements. We

know that we just have to deform the tuples to retrieve the values and the

NULL attributes, generating the SQL statements around isn’t hard. But here

comes the second reason why we need a proper data directory to do so, and why

the lack of DDL is important.

As you probably guessed by now, one critical piece of information needed for

the tuple deforming operation is the table structure declaration. Indeed,

the HeapTuple is just a big chunk of memory, and without the list of columns,

data types, and the types details, it’s impossible to interpret those. If your

model doesn’t change too much it’s probably possible to do without and instead

generate some kind of mapping manually based on what you know about the history

of the instance. Be careful if you go this way, any discrepancy between the

original and generated data types can lead to bogus output in the best case, or

crashing your whole instance. But in my case I had the guarantee that no DDL

happened since the incident, and the other data directory available so I could

just rely on it.

Postgres handles the table structure declaration using another struct, called

TupleDesc, for tuple descriptor. Its definition is:

typedef struct TupleDescData

{

int natts; /* number of attributes in the tuple */

Oid tdtypeid; /* composite type ID for tuple type */

int32 tdtypmod; /* typmod for tuple type */

int tdrefcount;/* reference count, or -1 if not counting */

TupleConstr *constr; /* constraints, or NULL if none */

/* attrs[N] is the description of Attribute Number N+1 */

FormData_pg_attribute attrs[FLEXIBLE_ARRAY_MEMBER];

} TupleDescData;

In our case the most interesting members are the number of attributes (natts)

and the array of pg_attribute records (attrs). Those are also useful for

the SQL generation part, as we can retrieve the columns from it. Note also

that postgres will generate a TupleDesc automatically when you internally

open a relation.

Let’s recapitulate. We have the record data, the filename contains the physical file location information that we can use to retrieve the actual relation, we know how to get the tuple descriptor for this relation and we can use it to deform the tuple and get the values from it. We have almost everything we need to generate the SQL queries.

The only remaining detail is that the values we get from the tuple deforming

operation are in their physical representation, and we need to emit their

textual representation. Again, that’s not a problem as each data type has a

dedicated function for that, called type output function, available in

pg_type.typoutput.

Extracting SQL from the INSERT records

Now is time for the fun part where we just need to put everything together to finish the project!

I chose to write it as an extension to be able to add and remove it easily from a production server. I also chose to minimize the amount of C code and rely on plpgsql functions when possible. It’s faster to write and plpgsql is also way safer.

I only wrote a single pg_decode_record() C function, that takes as input a

record as a bytea, the tablespace oid and the relation filenode and emits the

underlying SQL query. I wrote an extra pg_decode_all_records() function in

plpgsql that uses existing pg_ls_dir() and pg_read_binary_file() to

retrieve the files and record, and split_part() to extract the metadata from

the filename.

I’m attaching the resulting extension to this article so you can see the whole implementation and adapt it if needed, and will just quickly describe the main parts here as we already covered the underlying elements. I’m also only showing here a simplified version to avoid too many implementation details.

First, I look for a matching relation oid in the pg_class catalog for the given tablespace and relfilenode, open the found relation with the weakest lock possible, make a copy of the tuple descriptor and start generating the SQL query with the qualified relation name. As for normal application, you need to make sure that the identifiers are properly quoted to generate working queries:

PGDLLEXPORT Datum

pg_decode_record(PG_FUNCTION_ARGS)

{

bytea *record = PG_GETARG_BYTEA_PP(0);

Oid spc = PG_GETARG_OID(1);

Oid relfilenode = PG_GETARG_OID(2);

/* Get the relation oid from the tablespace oid and relfilenode */

relid = get_spc_relnumber_relid(spcOid, relNumber);

relation = table_open(relid, AccessShareLock);

tupdesc = CreateTupleDescCopy(RelationGetDescr(relation));

/* Start generating the SQL query */

initStringInfo(buf);

appendStringInfo(buf, "INSERT INTO %s.%s",

quote_identifier(get_namespace_name(RelationGetNamespace(relation))),

quote_identifier(RelationGetRelationName(relation)));

The next part extracts the data from the record and generate a HeapTuple with

just enough information to be correctly deformed:

/* mimic heap_xlog_insert */

data = VARDATA(record);

datalen = VARSIZE_ANY(record);

[...]

htup = &tbuf.hdr;

[...]

htup->t_hoff = xlhdr.t_hoff;

/* build a fake tuple with the bare minimum to deform it */

tuple = (HeapTuple) palloc0(HEAPTUPLESIZE + VARSIZE_ANY(record));

tuple->t_data = htup;

tuple->t_len = VARSIZE_ANY(record);

ItemPointerSetInvalid(&(tuple->t_self));

tuple->t_tableOid = relid;

For the next step, we just need to allocate the 2 arrays needed for the

deforming and call heap_deform_tuple():

values = palloc0(sizeof(Datum) * tupdesc->natts);

isnull = palloc0(sizeof(bool) * tupdesc->natts);

heap_deform_tuple(tuple, tupdesc, values, isnull);

Now that we have all the elements, we just need to iterate over the list of columns in the tuple descriptor, output a NULL if needed, otherwise find the type output function, call it for our value, and output it in the query after escaping it:

/* append the values */

appendStringInfoString(buf, " VALUES (");

for (i = 0; i < tupdesc->natts; i++)

{

char *value = NULL;

Oid typoutput;

bool typisvarlena;

if (i > 0)

appendStringInfoString(buf, ", ");

if (isnull[i])

{

appendStringInfoString(buf, "NULL");

continue;

}

getTypeOutputInfo(TupleDescAttr(tupdesc, i)->atttypid,

&typoutput, &typisvarlena);

value = OidOutputFunctionCall(typoutput, values[i]);

value = quote_literal_cstr(value);

appendStringInfo(buf, "%s", value);

pfree(value);

}

appendStringInfoString(buf, ");");

Once done, we just need to properly close the relation and return the generated query to the caller:

table_close(relation, NoLock);

PG_RETURN_TEXT_P(cstring_to_text(buf.data));

}

And that’s all you need for the basic scenario! The real implementation has a bit more code for various other cases, like very basic TOAST table support, but is still unlikely to correctly handle any weird corner cases that can happen in the wild.

Basic usage

We can finally see the result of all the hard work in this article and the previous one! I will be using a simple scenario, first saving the current WAL position to only keep the records generated afterwards, then removing all the data from the table (without changing its relfilenode) to make sure that we don’t read anything from the table itself.

-- Get the current WAL location

rjuju =# SELECT pg_current_wal_lsn();

pg_current_wal_lsn

--------------------

F/46349E80

(1 row)

rjuju=# CREATE EXTENSION pg_decode_record;

CREATE EXTENSION

rjuju=# CREATE TABLE decode_record(id integer, val text storage external);

CREATE TABLE

rjuju=# INSERT INTO decode_record

SELECT 1, 'simple test';

INSERT 0 1

-- Force a full-page write

rjuju=# CHECKPOINT;

CHECKPOINT

rjuju=# INSERT INTO decode_record

SELECT 2, 'full-page write';

INSERT 0 1

rjuju=# INSERT INTO decode_record

SELECT 3, 'a bit big '||string_agg(random()::text, ' ') FROM generate_series(1, 10);

INSERT 0 1

rjuju=# INSERT INTO decode_record

SELECT 4, 'way bigger '||string_agg(random()::text, ' ') FROM generate_series(1, 120);

INSERT 0 1

-- Check the heap table size and underlying TOAST table size

rjuju=# SELECT oid::regclass::text, pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(oid)),

reltoastrelid::regclass::text, pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(reltoastrelid))

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname = 'decode_record';

oid | pg_size_pretty | reltoastrelid | pg_size_pretty

---------------+----------------+-------------------------+----------------

decode_record | 8192 bytes | pg_toast.pg_toast_66731 | 8192 bytes

(1 row)

rjuju=# DELETE FROM decode_record;

DELETE 4

-- Make sure we remove all records and physically empty the tables

rjuju=# VACUUM decode_record;

VACUUM

rjuju=# SELECT oid::regclass::text, pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(oid)),

reltoastrelid::regclass::text, pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(reltoastrelid))

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname = 'decode_record';

oid | pg_size_pretty | reltoastrelid | pg_size_pretty

---------------+----------------+-------------------------+----------------

decode_record | 0 bytes | pg_toast.pg_toast_66737 | 0 bytes

(1 row)

Ok, we should have a few records generated in the WAL corresponding to data we definitely lost in the table. Let’s extract the INSERT records using the custom pg_waldump we created in the previous article:

$ mkdir -p /tmp/pg_decode_record

$ pg_waldump --start "F/46349E80" --save-records /tmp/pg_decode_record

[...]

$ ls -l /tmp/pg_decode_record

0000000F-46367520.1663.16384.66743.0_main

0000000F-46367660.1663.16384.66743.0_main

0000000F-46367738.1663.16384.66743.0_main

0000000F-46367868.1663.16384.66746.0_main

0000000F-46368130.1663.16384.66746.0_main

0000000F-46368300.1663.16384.66743.0_main

You might wonder why there are 6 records extracted while we only inserted 4 rows. That’s because the last record was big enough to be TOASTed using 2 chunks, and as far as the WAL are concerned that’s 3 separate INSERTs in 2 different tables. Let’s see that in detail using the extension to decode the records (truncating the output as some rows are quite big):

rjuju=# SELECT substr(v, 1, 95)

FROM pg_decode_all_records('/tmp/pg_decode_records') f(v);

substr

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

INSERT INTO public.decode_record (id, val) VALUES ('1', 'simple test');

INSERT INTO public.decode_record (id, val) VALUES ('2', 'full-page write');

INSERT INTO public.decode_record (id, val) VALUES ('3', 'a bit big 0.5356172842583808 0.3...'

INSERT INTO pg_toast.pg_toast_66810 VALUES ('66815', '0', E'\\x7761792062696767657220302e...'

INSERT INTO pg_toast.pg_toast_66810 VALUES ('66815', '1', E'\\x3337383137353120302e303439...'

INSERT INTO public.decode_record (id, val) VALUES ('4', /* toast pointer 66815 */);

(6 rows)

(note: I slightly edited the output to make it smaller and have correct syntax highlighting, the real extension will emit the real table name in a comment in case of INSERT in a TOAST table)

We see the first normal records properly decoded, whether they’re in a full-page image or not. The last record is indeed split into 3 different INSERTs, 2 in the TOAST table and 1 in the heap table.

As I mentioned earlier I only added very minimal support for TOAST tables, as I didn’t have any information about the customer tables and whether they would hit that case or not, or how often. The last insert isn’t a valid statement as the 2nd value is missing, but we can manually extract the value from the INSERT statements in the TOAST table and therefore fix the normal INSERT. For instance, using the first few bytes that we can see in the first chunk:

rjuju=# SELECT encode(E'\\x7761792062696767657220302e', 'escape');

-[ RECORD 1 ]---------

encode | way bigger 0.

The data is there, it just needs a bit of manual processing to get it.

To be totally fair, I also cheated a bit in that example by making sure that

the data will be TOASTed but not compressed, so it’s very easy to manually

retrieve the raw value from the extra INSERTs in the TOAST tables. It wouldn’t

be very hard to have all of that working transparently, but I simply didn’t

have the need. If you’re interested in that, I’d recommend looking at the

detoast_attr() function in

src/backend/access/common/detoast.c

and all underlying code to see how you can manually decompress data. You would

then only need to store the detoasted (and potentially decompressed) value

referenced by the toast’s chunk_id locally, and emit it in the query instead of

the currently emitted comment.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed those two articles and learned a bit about the WAL infrastructure and the way pages and tuples work internally.

If you missed it in the article, here is the link for the full extension.

I want to emphasize again that all the code I showed here is only a quick proof of concept that’s thought for one narrow use case, and it should be used with care. My goal here wasn’t to show state of the art code but rather show one possible way to quickly come up with a plan to salvage data in case of production incident. If you’re unfortunately confronted to a similar problem, or some major other accident I hope you will find some valuable resources and a starting point to come up with your own dedicated solution!